First things first, this author would warn the prospective reader that this analysis most certainly contains spoilers. Read at your own risk. Secondly, we must recognise that there are undoubtedly many quality reviews of the film out by now, but it is our hope that the angle from which this article covers the film (Barbie as an alternate story of Creation and Fall) will be one you won’t find anywhere else with this specificity. Furthermore, there is a warrant for taking this hermeneutic to Greta Gerwig’s film, since she revealed to Vogue in an interview that “That kind of creation myth (that of her film) is the opposite of the creation myth in Genesis.” So, with Gerwig’s blessing, let’s dive in.

We begin, where all things begin, in Genesis. Biblically (considering aspects of chapters 1-3), the story follows these beats:

- In the beginning there is God, and he creates an entirely good world.

- God creates a man called Adam, and then God creates a woman out of a bone from Adam’s body, and when God presents her to Adam, he names her Eve.

- A serpent inside the perfect walled garden introduces evil, shame, guilt, unhappiness and conflict by leading Eve and then Adam into sinful behaviour.

- One of the consequences of sin in the world is unfaithful Cain’s murder of his righteous brother, Abel.

Gerwig’s film subtly contains two parallel creation focusses, in a way meaningfully reminiscent of the different focusses of Genesis 1 and 2. In Gerwig’s first (and overarching) creation narrative, it goes this way:

- In the beginning there are little girls, and those little girls live in a barren wasteland where all they can do is play with baby dolls which represent their calling to motherhood.

- The proto-barbie is manifested in glory, awakening all the little girls to their true calling: playing with exciting new and various dolls that represent their calling to do whatever they like, whatever fulfils them as they see it.

- This vocational endowment leads the girls to the liberating destruction of their baby dolls.

There’s so much that could be said about this sequence alone, but before we consider the ‘second perspective’ creation story that the movie presents, consider what is being copied, and what is being subverted by Gerwig.

Scripture starts with the personal God creating a perfect world (Gen 1:1, 31). Barbie starts with an uncreated world which is also barren and unsatisfying. Scripture starts with Man being created (Gen 1:27, Gen 2:7), and given the calling to rule and care for the world (Gen 1:26, 28-30). Woman is created out of Man (Gen 2:21-23), and given the task of helping the Man so that he can thrive in his work (Gen 2:18). Barbie starts with women existing, and with no good purpose there to fulfil them until proto-barbie arrives, at which point their true calling essentially amounts to whatever they want it to be. In Scripture, it is sin that leads to Cain’s murder of Abel (Gen 4:4-8). In Barbie, it is liberation that leads to the girls’ destruction of their children. In truth, Cain was ungrateful to God, and this author would describe him as unwilling to thrive in the blessings that God ordained for mankind in creation. In the same way in Barbie, the first girls are ungrateful and unwilling to thrive in an unmissable aspect of their calling: motherhood.

The Biblical first creation story is big-picture (Gen 1:1-2:3), and shows the creation of the world and the order of those in it. The second creation story is more personal (Gen 2:4-25), and focusses on the relationships between the three characters, God, Adam and Eve. In the same way, the second creation paradigm offered by Gerwig’s film (as this author delineates them) is also the more personal one, and one that focusses on life in the Garden.

Ok, take two. Let’s look at the second creation story in Scripture, and how that compares to the equivalent main beats in Barbie.

- Eden is a perfect walled garden.

- There is a serpent in the garden that tricks the perfect man and woman into disobeying God.

- This disobedience introduces the discord of sin into the garden, and into the whole world.

In Barbie, this is how it happens.

- Barbieworld is a perfect self-contained world.

- The perfect women in the garden do nothing wrong. A morally complicated human outside of Barbieworld acts upon a barbie doll (which is essentially functioning like a Voodoo doll) in a way that affects Barbieworld, introducing corruption, discord and displeasure into Barbie’s perfect world.

This comparison draws out one of the very interesting fundamental narrative differences: Barbieworld is a walled garden with no snake. All barbies are ‘self-unconscious’ (cf. Gen 3:7) until Barbie first describes having a kind of awareness where she is aware of herself (loosely paraphrased). Until then, there is no sin in the garden, and Barbie walks joyfully in the light of the day.

A quick side note: this author argues that the so-called paradise barbie lived in was actually rather nightmarish, since Adam’s garden was a very real and tangible place where work could be done, food eaten, sexual intercourse enjoyed, dirt gotten under fingernails, etc; but Barbie’s garden was a set intentionally devoid of the traditional ‘four elements’ (water, fire, earth, wind), according to Gerwig’s design. As a result, even the supposedly perfect, sublime and ideal Barbieworld has the eerie quality of a dystopian utopia (e.g. The Truman Show, certain seasons of AMC’s The Walking Dead, Westworld, The 100 season 6, etc).

So, in Barbie’s sinless garden, it’s not a snake that tempts the woman, but it is actually the complicated emotions of a mother struggling to connect to her daughter which are projected onto Barbie, which introduce sin, cause the fall, and lead to barbie feeling self-conscious, and ‘flat footed’.

This article does not have room to begin to draw out all of the possible readings, angles and connotations that this author immediately thought of when he first saw this, but suffice it to say that this lets the interpreter posit the ‘real world’ in the Barbie film as a kind of higher order reality which affects what takes place in Barbieworld—which becomes an entirely contingent system. However, we think that this reading begins to diverge too greatly from our stated goal, so let us ignore that rabbit hole, and keep plodding along.

Barbie’s fall into imperfection takes on a few entertaining and whimsical forms, one of which is that her feet are no longer permanently in the rather unnatural position needed for wearing high heels, but are now flat, or in other words, normal. This symbolises not only her departure from ‘toy’ to ‘real woman’, but from being ‘in the sky’ to ‘in touch with the earth’. This is emphasised by the thud that the viewer hears the first time that her heel lands ominously on the ground. Something deeply consequential, world shattering, paradigm shifting has happened. What is it? Just a lady whose feet are now normal. O patient reader, do you see just how much fodder for analysis is this film? We will not at all be surprised to see it remain in years to come as a favourite of the students of film analysis.

Barbie’s meeting with her Creator, Ruth, was literally her ‘meeting with God’ scene. The blank white space in which she interacts with Ruth is reminiscent of this narrative function in several other films: Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 2, The Matrix, The Matrix: Reloaded, arguably Stranger Things also.

Whereas Adam was created first with a dominion mandate, and Eve created from and for Adam (1 Cor 11:8-9), and to walk alongside him in the cultural mandate, Barbie was created by Ruth with no intended purpose or telos, and Ken was created to only really feel alive when receiving Barbie’s fickle praise and attention.

This author thinks that most reviews of this film, even ones with a distinctively Christian framework, pass over this: the modern world has sold us the lie that being created with a purpose or role in society and the world is too restrictive, and stifles a person’s need for self-discovery and self-expression, when the truth is to be found in what Barbie discovers—all created people desire to have a connection with their creator, and know what their created purpose is. This author felt bad for Barbie as her creator Ruth told her that whilst all the other barbies had a particular profession or gimmick, she was just Barbie, she was the tabula rasa Barbie, it was entirely up to her.

If that’s bad enough for Barbie, it has downstream consequences for Ken. He only truly lives when he has her attention and affirmation. Eve was not like this at all. She was a true human regardless of Adam’s fixed or waning attention, even granting that her God-given role was to help him. Ken is dependent on the fickle Barbie for his fulfilment, and she is dependent on her passing whims for any sense of her own fulfilment.

Dear reader, please see this! The anthropology in Barbie is truly hopeless. It gives shape to the hopeless structure implicit in the atheistic and egalitarian reduction of the human person that has taken root in our society. We recognise that the last stages of the film attempt to resolve or improve or turn around the role of Ken in relation to Barbie and the world, and there are valid arguments to be made about what Barbie’s visit to the gynaecologist at the end of the film says about the telos she chooses for herself, but regardless, at the end of the day these characters are left to write their own story. Dear reader, let it be carried without dispute that Aragorn and Frodo’s journey wouldn’t seem nearly so heroic if they were bored one day and just decided that heating up a metal ring sounded like a good life goal. A meaningful and heroic destiny is not one you make up for yourself.

For those longsuffering readers who are still on the train of this winding theological allegory, this author would table the possibility that Ruth’s lack of knowledge of Barbie’s purpose and ‘ending’ is essentially open theism, which is a deeply false theological system in which God is not all-knowing, but learns new information as his totally autonomous creatures make decisions he neither plans nor predicts. Thank God that this is not the truth.

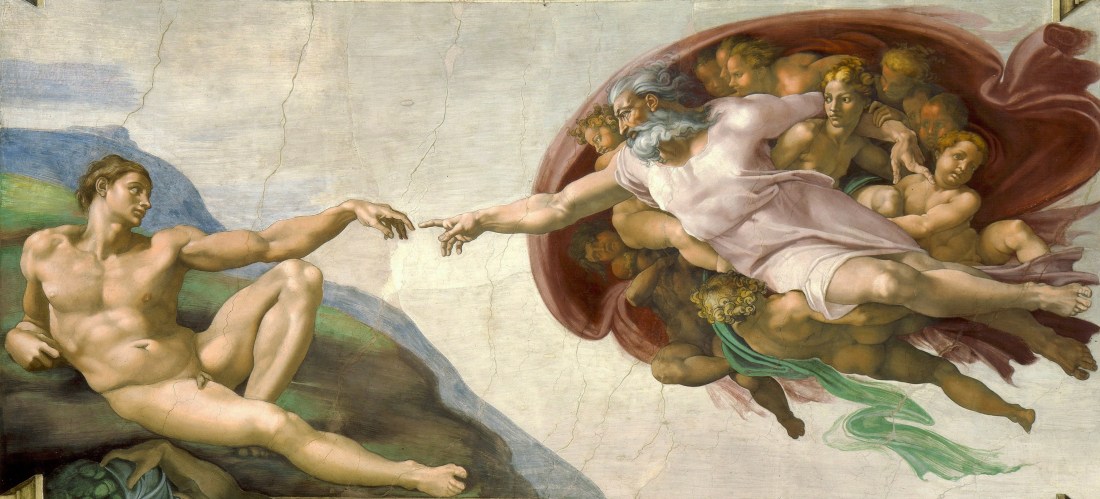

This author has titled this article partially in reference to The Creation of Adam, a famous painting in which the hands of Creator and Creature touch, and Adam receives the communicable attributes of God (ok, let us admit that this is our interpretation). We made this decision because the Barbie film has brought lots of subjects into the spotlight, but the subject that we contend is so culturally turbulent at the moment and which is also key to this film is this: What is a human? What are they for? So, it is very significant that Barbie is getting us to discuss ‘what is a real woman?’ and ‘are people created with a purpose?’. All the discussions around feminism and egalitarianism and patriarchy and all that are secondary to the anthropological question of human nature.

Let’s wade for a moment in more perilous waters. A pervasive theme in Barbie is ‘patriarchy’, but to the movie’s credit, it isn’t nearly as lame about it as many feminist propaganda films. The association of the patriarchy with men riding horses and ruling the world lets the reader know that Gerwig is not trying to be too serious in her portrayal of it, but is rather having fun with a humorously simple version of patriarchy.

Now, clutch your pearls or what have you, but it seems obvious to the student of history or Scripture that Patriarchy is an inherent structure in the world as God designed it (1 Cor 11:7-12, Col 1:15-18, Eph 5:22-33, Mark 12:26, Matthew 22:24, Lev 25:47-55, Ruth 3:9, etc). If you take the time to read those references, you will likely be very confused, and think that this author is off with the fairies. However, that is because a biblical definition of Patriarchy differs totally from the pervasive secular one.

Being no expert, let us posit a working definition. Biblically, Patriarchy could be considered as being the inescapable reality inherent to the following facts:

- God reveals himself to us in masculine terms (Gen 1:27, 1 Cor 12:11) This is not simply anthropomorphic language on the part of human writers to try to describe God in their own words, because it is also his word, so it can be relied on as accurate. This is of course not to say that either the first or third persons of the Trinity are human men, this is true the second person alone, but that the masculine pronouns alone are proper to use of God.

- The Father’s relationship with his Son is beautifully and properly one of headship and submission (Luke 22:42). This shows that in the intra-trinitarian life, the structure of two persons of equal power, value and dignity having different roles, which are accurately distinguished as being differences of rank, or order, or leadership, is a perfectly good and beautiful thing.

- Christ is the head of his body, which is the Christian church (Eph 5:23). He is not just the head of the body, but as the creator and saviour and redeemer of it, he has absolute say in regards to the proper behaviour, governance, activities etc of his body.

- God created Adam first, and created Eve for Adam (1 Cor 11:8-9), and as a helper for Adam in his mission (Gen 1). The focus of the biblical narrative is around men being given a mission and authority and responsibility to be in charge of cultivating the wild earth, raising and loving a family, and teaching the generations to know and love the Lord. The first man, Adam, does not complete this mission. The second Adam, who is Christ (1 Cor 15:45, 47) takes this mission and responsibility onto himself, and completes the mission, slaying the dragon, and in the process receives the reward of a perfect bride, presented to him and for him.

There are so many other points to make, but let us get to the point. We see that God the Father exercises authority over God the Son. Then God the Son exercises authority over all creation and in particular, his bride, which is all who worship God. The husbands and fathers in that ‘bride’ exercise authority over their wives, children, congregations, property and animals.

This is the fundamental order that exists, and receives his blessing, in the home and the church explicitly. This is what this author would refer to as the Biblical and intrinsic and inevitable patriarchy, and it is a wonderful thing, because God made it.

It is no surprise that women, who will necessarily represent the majority of primary carers in domestic and childcare environments, will not also have majority or be at parity with men in terms of vocationally participating in all of the governing structures of society. God calls men to rule the world, and to love their wives the way Christ loved the church. Men ruling the world does not equal women being slaves. In fact, is it in the lands that have been most deeply soaked in the Protestant faith that historically women have enjoyed the greatest freedom. The biblical order of Patriarchy actually frees women far more than any modern contrivance of envy ever could.

To conclude this section, let the reader simply note that Gerwig set up a fun but silly version of the patriarchy in her film as something not to be desired. We consider this a winsome way to make her point without it becoming a trite diatribe, and nonetheless gently remind the reader that a different, good and biblical concept of patriarchy still remains intact after the viewing of Barbie.

One scene in the film calls for a special mention: the woman played by actress America Ferrera has this awful monologue which is preachy in all the wrong ways, and totally misses the tone of the film. However, it is a good example of the mixed messaging that the girls of our generation are getting. Below, this author will give examples of the kind of statements (not exact quotes) that Ferrera’s character complained about, and consider their implications.

- ‘Be whatever you want to be.’ This sets the bar way too low, because it lets a girl never try, never learn, never push herself, and then tells her that she can find fulfilment and satisfaction like that. As we’ve seen, this maxim gives no structure or direction or true freedom. This is the kind of line you expect to hear from companies like Nike or Disney.

- ‘You have to be a CEO and a lawyer and a nobel prize winner’. This sets all women up for disappointment (by setting a bar so high that few women will hit it) and loneliness (because of the relational sacrifice necessitated in rising to the uppermost echelons in highly competitive fields). This is asking them to essentially perform like a tiny minority of high-tier men if they are to be accepted as successful women, and is a shocking burden to place on someone.

- ‘Be a mother and a volunteer and a businesswoman’. This mistakenly categorises motherhood as just one scheduling item alongside other items like volunteering or leading a business. A woman might be able to run a business full time, and fit in two hours on Saturday to volunteer at an op shop, but being a mother is not comparable to those other things. You can’t just choose a few hours here and there to do ‘motherhood’ and the rest of your time be something other than a mother. Motherhood is a beautiful and profound vocation, one that deserves full time availability (though this author recognises that not all mothers have this privilege), and if you try to add in other jobs and other responsibilities, you run the risk of spoiling all of those pursuits. There is no way that some business or CEO will reward you for your time more than a little flock of immortal souls that you created with the man you love.

So, even after only a brief consideration, it is true and fair to say that the girls of today are getting hopelessly mixed messages, and that they need and deserve better. Ferrera was right about that. However, what good would a doctor be if she could diagnose the issue but was stumped for a solution? We are right to look elsewhere for the answer to the problem girls are facing, because Ferrera and Gerwig did not and do not have the answer.

To bring this contemplation to a close, let’s summarise what we have said so far.

- Barbie presents a fundamentally different creation myth to the one seen in Scripture.

- The purposelessness of Barbie and Ken is one of the saddest things about the film, and to that extent one of its worst lies.

- The patriarchy rejected by modern feminism truly is partially worth rejecting, but a biblical framework and concept of patriarchy is not only good, but inevitable.

- Girls and young women today are being presented with so many conflicting messages about how they should live. However, the clear answer and the right path are not found in the Barbie film, but only to be found and enjoyed fully in the context of a life powerfully changed by the risen Lord, Jesus Christ.

This author plans to watch the film again, probably multiple times. It was fun. But let our appeal ring clear. Dearest Barbies and Kens reading this, you will only find true life, life that satisfies unfadingly, imperishably, perfectly, in submission to the Man, Jesus of Nazareth.